|

The Interwar Years

With the end of the First World War in November 1918, the urgent work of Fort Slocum ended. The U.S. Army shrank rapidly, dropping from a peak of 3.7 million to around 144,000 soldiers in 1922-1935.

The Army still had a continuing need for new recruits, and during the 1920s and 1930s Fort Slocum received and processed them as it had for decades. Organizational changes, however, meant that the post operated as a training center under a regional command, rather than as part of the Army’s General Recruiting Service.

Fort Slocum also served as the eastern U.S. assembly point for recruits bound for posts overseas. Recruits from everywhere east of the Mississippi River traveled to the post to be sent to Puerto Rico, Panama, Hawaii, the Philippines and China.

In the late 1920s the Quartermaster Corps established one of its bakers and cooks schools at Fort Slocum (in operation ca. 1928-1943). Its students learned to plan, prepare and serve meals for hundreds of soldiers at a time, essential tasks for keeping the Army functioning. This technical school was the first to be housed at Fort Slocum. Others would follow during the Second World War, and they would comprise the post’s entire mission in the 1950s and 1960s.

Occasionally during this period Fort Slocum also hosted non-military activities. It provided training facilities for the 1920 U.S. Olympic team and for New York University’s football team in 1922 and 1925.

In the 1930s Fort Slocum was one of several posts around New York that received men newly enrolled in the Civilian Conservation Corps (1933-1942). The CCC put tens of thousands of unemployed to work on reforestation, park construction, conservation and similar projects in rural areas around the nation. At Fort Slocum and other posts, the Army clothed, fed, and conditioned the men into companies before sending companies of them to nearby and distant work camps.

Until the mid-1930s, the Army’s budgets were lean, and major construction projects were rare. In the interwar years post commanders restored the grounds, which had been so heavily used during the First World War. They also gradually removed most of the war’s temporary buildings.

Recognizing acute shortages of housing for enlisted personnel, Congress authorized some new construction at Army posts beginning in the late 1920s. This funding allowed construction of two new barracks (Buildings 58 and 60) and four duplex family quarters for noncommissioned officers (Buildings 104-107) at Fort Slocum around 1930. About this time the Army also replaced the brick water tower built in the 1880s at the southern end of Davids Island with a larger steel water tower (Building 45, completed 1929) located at the island’s northern tip.

The Army’s funding began to increase after 1935, and a major program of improvements at Fort Slocum began, lasting into the Second World War. Many buildings were modernized, and several new ones, including the last of the permanent barracks (Building 59), were built. The sewage system and roads were also improved.

Cooks, Railroaders and Wacs (1922 - 1946)

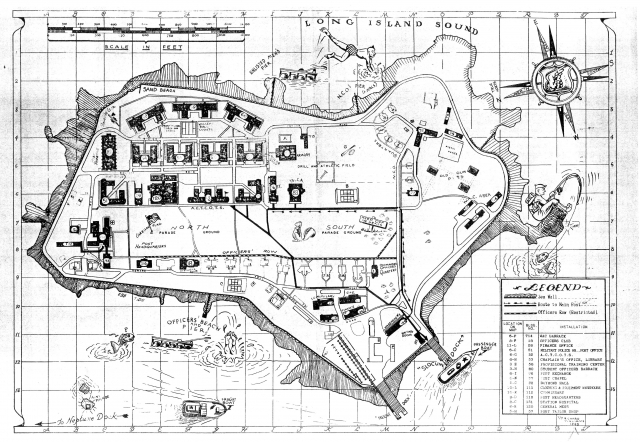

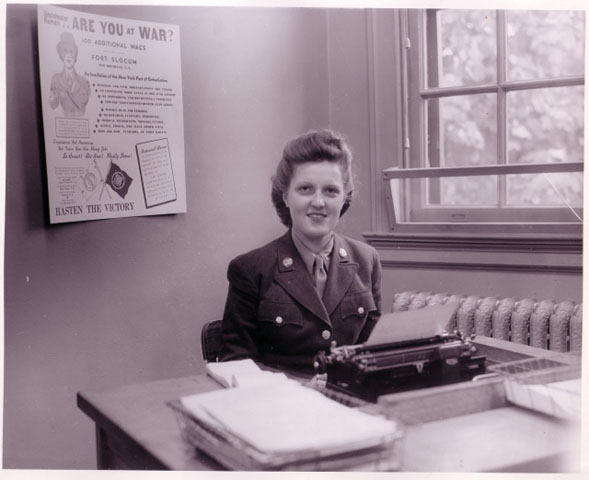

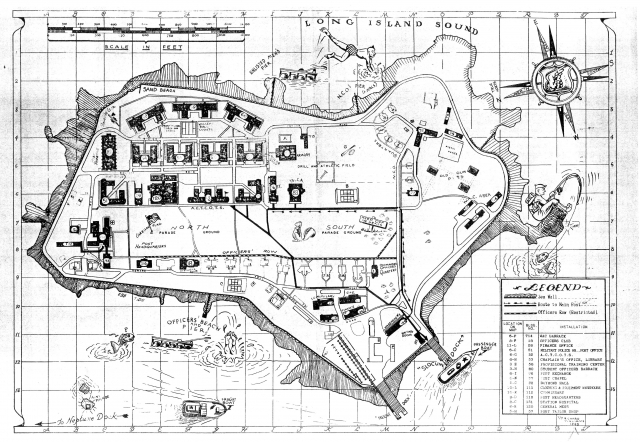

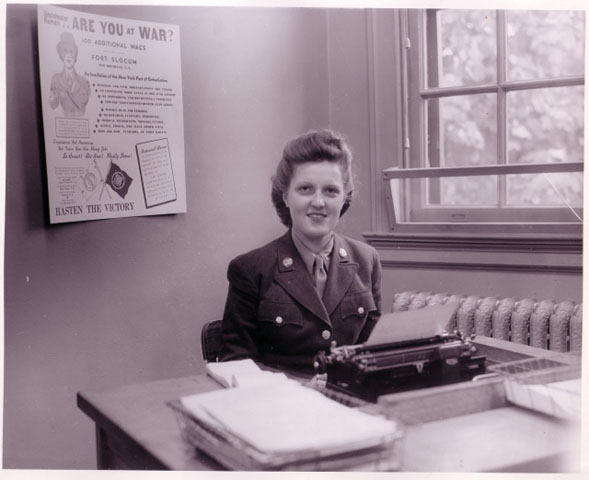

ACTCOTS Guide Map Ft Slocum 1943Guide map of Fort Slocum, Davids Island, prepared for the Atlantic Coast Transportation Corps Officers Training School in 1943.   ACTCOTS logo B&W"Keep 'Em Moving:" a slogan of the Atlantic Coast Transportation Corps Officers Training School, at Fort Slocum 1942-1944.   AfAm Cooks & Bakers School apr 1941 butcheringSince the Army remained segregated until 1947, black soldiers attending the Bakers and Cooks School at Fort Slocum, shown here in 1941, attended classes separate from their white counterparts.   baking piesBaking pies in the Army Bakers and Cooks School, which operated at Fort Slocum during the 1930s.   bldg 52 ACTCOTS from Casual NewsBuilding 68, then designated as Building 52, originally a barracks, was the main building of the Atlantic Coast Transportation Corps Officers Training School, 1942-1944.   Col Lentz takes salute WACsCol. Bernard Lentz, Fort Slocum's commanding officer 1942-1945, reviewing a platoon of the Women's Army Corps on the Parade Ground during the Second World War.   Italian POWs moving cratesAn Italian Service Unit comprised of prisoners of war was assigned to Fort Slocum in 1944 to provide labor in support of the post's wartime activities.   Motor pool men & women on vehiclesThe Wacs and male soldiers of Fort Slocum's motor pool during the Second World War.   WAC basketball teamWacs at Fort Slocum formed a basketball team and played against teams from other posts during the Second World War.   WAC w WAC recruiting poster tea 11 jun 1944WAC typist with Fort Slocum recruitment drive poster, 1944.   Platoon S Side Blg 61 late 1930s front 4-5kcTaken in the spring of 1942, this photo postcard may show the combat platoon organized early in the Second World War to protect Fort Slocum from saboteurs and commandos. The men stand south of Buildings 61 (left) and 59-60 (right). With equipment spanning 30-plus years of Army designs—from 1903 Springfield rifles through 1917 Brodie helmets and water-cooled machine guns (on carts) to 1930s uniforms—the platoon embodies the American soldier in transition from doughboy to GI.   RoosvFA CCC_recrts_to_Slocum_1933 NYWTS-NewsPhoto Boarding a bus in June 1933 bound for Fort Slocum, these veterans of the First World War from New York City had just been accepted for dollar-a-day jobs in the new Civilian Conservation Corps (Library of Congress, Prints & Photos Div, NY World-Telegram & Sun Newspaper Photos digital collection).

The Second World War

During the Second World War life at Fort Slocum was busy and diverse. Although the Army made heavy demands on the post, there was less wear and tear on the installation because of improved logistics and efficiency and because the post’s missions were better suited to its capacities and limitations.

Westchester County supported Fort Slocum in many ways. Its citizens served as civilian workers on the post, joined the Army during local recruiting drives, purchased war bonds and hosted social events for soldiers. Some activities from the period left enduring legacies, like a project by New Rochelle artists to make sketch portraits of Fort Slocum personnel. Ten scrapbooks of these portraits are now in the collection of the New Rochelle Public Library.

The post’s most important role was as a staging area for troops. The post provided temporary quarters, medical services and supplies for groups of soldiers headed overseas. It was also a rest station for Allied troops in transit and a processing center for returning American personnel.

In addition, Fort Slocum continued to serve as a recruit intake and specialist training center. It was the site of the Atlantic Coast Transportation Corps Officers' Training School from 1942 to 1944. The school trained railroad men and other transportation specialists in the Army way of doing things before making them commissioned officers. A related program begun in 1943, the Provisional Training Center, provided basic training to other specialists and enlisted men.

One of the lasting contributions to Army life that emerged from Fort Slocum during the Second World War was the Duckworth Chant. In this chant, a leader alternates calls with his or her unit to provide cadence during marching and drilling. It was developed by a Fort Slocum drill instructor in 1943, Pvt. Willie Duckworth, and promoted by the post’s commanding officer, Col. Bernard Lentz, a former drill master. Today, many Americans instantly associate the sound of this chant and its endless variations as part of the soundscape of military posts.

In 1944 Fort Slocum also became home to a group of Italian prisoners of war. After Italy surrendered in mid-1943, the Army recruited some 35,000 of the 50,000 Italian POWs in the U.S. as volunteers for farm work and other labor. Organized into groups called Italian Service Units, these volunteers did jobs like freight handling, deck loading, cooking and laundry. Many continued to live in their POW camps but under relaxed security, while others, like the group at Fort Slocum, were relocated to quarters near their work assignments.

Fort Slocum’s experience with these tasks led to its assignment as the regional Army rehabilitation center in 1944 to 1946. The center, previously located at Camp Upton on Long Island, retrained court-martialed soldiers in lieu of sending them to military prison.

Like many posts in the U.S., Fort Slocum participated in one of the Army’s great personnel experiments of the period. During the Second World War large numbers of women served for the first time as members of America’s armed forces. Army servicewomen, or Wacs, belonged to the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), originally called the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC).

Wacs arrived at Fort Slocum in May 1943. They served as file clerks, typists, stenographers, messengers, telephonists, mess hall staff, motor pool drivers, training instructors, morale and recreation personnel, and hospital technicians and orderlies. Their range of duties expanded as they gained experience in Army life and earned the confidence of their male counterparts. They participated fully in the social and ceremonial life of the post, from dances and theatricals to athletic contests and drills. They recruited, sold war bonds and sang with the post’s band.

The Army undertook only modest construction projects at Fort Slocum during the Second World War. A few temporary buildings were erected, but not nearly so many as during the previous war. Part of the Mortar Battery was demolished to create a firing range for small arms practice. A cluster of buildings (Buildings 130, 131, 133-135) was erected to house the post’s contingent of Wacs.

|

Cooks, Railroaders and Wacs (1922 - 1946)

Cooks, Railroaders and Wacs (1922 - 1946)